When you pick up a prescription at the pharmacy, you might not realize there are two kinds of generic drugs on the shelf-and they can cost very different amounts. One is made by the original brand-name company and sold under a generic label. The other is made by a rival company that was first to file paperwork with the FDA. These are called authorized generics and first-to-file generics. Understanding the difference isn’t just for pharmacists or insurers. It affects how much you pay out of pocket, how much your insurance covers, and even how quickly cheaper options become available after a brand drug loses patent protection.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic is the exact same drug as the brand-name version, made by the same company, in the same factory, with the same ingredients and packaging-except it doesn’t carry the brand name. It’s sold under a generic label, often at a lower price. For example, if you buy the authorized generic version of Lipitor (atorvastatin), it’s made by Pfizer, just like the brand version, but it’s labeled as "atorvastatin calcium tablets." These drugs enter the market under the original brand’s New Drug Application (NDA), so they don’t need to go through the full FDA approval process that traditional generics do. That means they can appear on shelves faster than regular generics. Sometimes, they show up even before the first traditional generic hits the market. Brand manufacturers often launch authorized generics as part of legal settlements with generic companies to avoid long court battles. It’s a way for them to keep some of the market share while letting competition lower prices.What Is a First-to-File Generic?

A first-to-file generic is the first company to submit an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to the FDA after a brand drug’s patent expires. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, this company gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell its generic version-no other generic can compete during that time. This exclusivity is a huge financial incentive. For blockbuster drugs, those 180 days can mean hundreds of millions in revenue. During this window, the first-filer has no competition. That gives them pricing power. They can set the generic price at a discount to the brand, but not necessarily the deepest discount possible. The FTC found that in markets with only one generic (the first-filer), the average retail price is about 14% below the brand price. That’s a good deal, but not the best you can get.Why Authorized Generics Change the Game

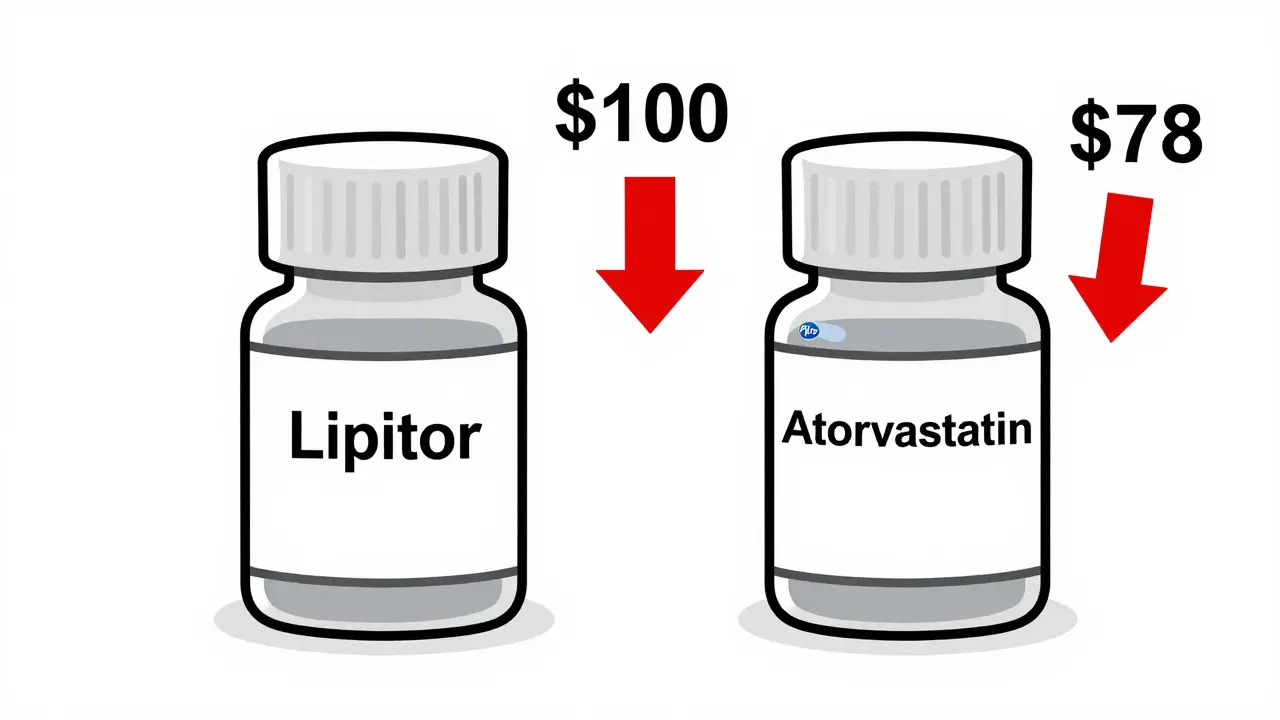

Here’s where things get interesting. The 180-day exclusivity for first-to-file generics doesn’t block authorized generics. So if the brand company launches its own generic version during that window, it creates a two-player market. And that’s when prices really drop. According to the FTC’s 2013 report, when an authorized generic enters the market during the first-filer’s exclusivity period, retail prices for generics fall by 4% to 8% more than they would without it. Wholesale prices drop even more-by 7% to 14%. In one analysis of 95 drugs, pharmacies paid 27% less than the brand price when both types of generics were available. Without the authorized generic, that number was only 20%. That difference might sound small, but multiply it by millions of prescriptions, and you’re talking about billions in savings for patients and insurers. For example, if a brand drug costs $100 per month, a single generic might cost $86. Add an authorized generic into the mix, and the price can drop to $78 or lower. That’s a $8 monthly saving per person. For someone on a chronic medication, that adds up to $96 a year-just from one extra competitor.

Who Benefits the Most?

The biggest winners are patients and payers like Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers. Lower prices mean lower out-of-pocket costs and smaller claims bills. Pharmacists also benefit. Gross profit per prescription goes up when two generics compete. Even though each pill sells for less, the volume increases, and the margin per unit stays strong-or even improves. The first-to-file generic doesn’t win as much. Their revenue drops by 40% to 52% during the 180-day window when an authorized generic enters. That’s a massive hit. But here’s the twist: that doesn’t stop companies from filing first. The FTC studied this for years and found no evidence that authorized generics discourage generic manufacturers from challenging patents. In fact, the incentive to be first remains huge because of the potential for massive profits during exclusivity. Brand manufacturers also benefit. They get to keep some control over the market, collect revenue from their own generic, and avoid being completely pushed out. Plus, they can use the launch of an authorized generic as a tool in patent litigation settlements. It’s a strategic move that lowers legal risk while still letting competition happen.Price Differences by Market Size

The number of competitors has a direct effect on how low prices go. The FDA analyzed data from 2015 to 2017 and found a clear pattern:- One generic (first-to-file only): 39% lower than brand price

- Two generics (first-to-file + authorized generic): 54% lower

- Four generics: 79% lower

- Six or more generics: over 95% lower

Are Authorized Generics Slowing Down Generic Competition?

Some critics worry that if brand companies can just launch their own generics, they might discourage other companies from filing ANDAs. The idea is: why risk a costly lawsuit if the brand will undercut you anyway? But the data doesn’t back that up. The FTC’s long-term analysis found no measurable drop in the number of patent challenges by generic companies. Even with authorized generics in play, firms still file ANDAs. Why? Because the 180-day exclusivity is still worth it. If you’re first, you get to be the only one selling for half a year. That’s a huge reward. Also, authorized generics aren’t always launched. They’re a tool, not a rule. Brand companies use them strategically-often only when they’re settling lawsuits or when they want to protect their market share without triggering a full-price war.

What About the Long Term?

Some authorized generics disappear after a few months. Health Affairs research from 2023 found that about 20% of authorized generics launched between 2010 and 2014 had no sales in Medicare data after five years. That means they were temporary. They served their purpose: drive down prices during the critical early window, then fade out. Meanwhile, traditional generics keep coming. With the FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), approval times have dropped by about 13 months since 2012. That means more generics enter faster overall. The combination of faster approvals and authorized generic competition has made the market more dynamic than ever.What This Means for You

If you’re paying cash for a prescription, ask your pharmacist: "Is there an authorized generic available?" Sometimes, it’s the cheapest option-even cheaper than the first-to-file generic. You might not even know you’re getting it, because it’s labeled just as "atorvastatin" or "metformin." But if you ask, they can tell you. If you’re on insurance, your plan might already be using authorized generics to keep costs down. You might not see the difference on your receipt, but the savings are there. The bottom line? More competition = lower prices. Authorized generics don’t replace first-to-file generics-they make them compete harder. And that’s good news for anyone who needs medication.How to Spot an Authorized Generic

There’s no universal label, but here are ways to identify one:- Ask your pharmacist: "Is this made by the brand company?"

- Check the manufacturer name on the bottle. If it’s the same as the brand (e.g., Pfizer, AbbVie, Novartis), it’s likely an authorized generic.

- Look up the drug on the FDA’s Orange Book. It lists which companies make authorized generics.

- Compare prices. If the generic is significantly cheaper than others on the shelf, it might be an authorized version.

Are authorized generics the same quality as brand-name drugs?

Yes. Authorized generics are made in the same facility, with the same ingredients, and under the same quality controls as the brand-name drug. The only difference is the label. The FDA treats them as identical to the brand.

Why would a brand company sell its own generic?

Brand companies launch authorized generics to reduce legal risk, maintain some market share, and avoid being pushed out completely. It’s often part of a settlement in patent lawsuits. They still make money, but they let competition lower prices-which benefits consumers.

Do authorized generics delay other generics from entering the market?

No. Studies by the FTC show that authorized generics don’t reduce the number of patent challenges or delay other generics. In fact, they often speed up competition by lowering prices early and encouraging more companies to enter.

Can I ask for an authorized generic at the pharmacy?

Yes. You can ask your pharmacist if an authorized generic is available. It’s often the lowest-priced option, even during the first 180 days after a brand drug goes generic. Just say, "Is there a version made by the original company?"

Are authorized generics covered by insurance the same way as other generics?

Yes. Insurance plans treat authorized generics the same as any other generic drug. They’re listed in formularies as generics and usually fall into the lowest copay tier. You won’t pay more for an authorized generic than for a traditional one.

holly Sinclair

December 17, 2025 AT 16:23It’s fascinating how the pharmaceutical industry operates like a chess game where the players are corporations and the pawns are people who need insulin or blood pressure meds. Authorized generics aren’t just a market quirk-they’re a structural hack in the system, designed to simulate competition while letting the original monopolist still profit. It’s capitalism with a smiley face, but the smile is painted on a skull. We celebrate lower prices, sure, but we rarely ask why the system was built this way in the first place. Why should a company that invented a drug be allowed to *also* be the first to undercut it? That’s not competition-it’s consolidation dressed in a white coat.

Monte Pareek

December 17, 2025 AT 17:07Look I’ve been in pharma for 20 years and let me tell you this right now the authorized generic is the secret weapon that actually saves lives not the first filer the first filer is just a glorified rent-seeker with a 180 day monopoly and yeah they make bank but the authorized generic drops prices faster and deeper and that’s what matters for the guy on Social Security trying to afford his statin. If you’re not asking your pharmacist if it’s made by the brand you’re leaving money on the table and that’s on you not the system

Kelly Mulder

December 18, 2025 AT 23:39It is, of course, profoundly ironic that the very entities responsible for inflating drug prices to astronomical levels are now the ones ‘saving’ consumers by selling their own generics. The hypocrisy is not merely aesthetic-it is ontological. The FDA, in its infinite wisdom, permits this duality under the guise of ‘efficiency,’ when in reality it is a regulatory capture masquerading as market innovation. One cannot help but wonder: if Pfizer can make a generic of Lipitor, why did they charge $200 per pill for a decade? The answer is simple: because they could.

Tim Goodfellow

December 20, 2025 AT 12:11Man this is wild-like watching two wolves fight over a carcass and then one wolf suddenly says ‘hey I’ll just chew it slower so you think you’re winning’ and then drops a second wolf into the mix to make the whole thing collapse into a feeding frenzy. Authorized generics? That’s not competition, that’s corporate sabotage with a PR team. But hey, if it drops my metformin from $80 to $40, I’m not complaining. Just wish the system didn’t have to be this convoluted to make medicine affordable. We’re not fixing the machine-we’re just duct-taping it while it explodes.

Takeysha Turnquest

December 20, 2025 AT 16:23It’s not about the price it’s about the power the brand companies hold the FDA holds the pharmacies hold and we hold nothing. We are the last link in a chain that was never meant to serve us. The authorized generic is a whisper of rebellion from within the machine-but it’s still the machine. And when the whisper stops, we’re back to paying $120 for a pill that costs 3 cents to make. I feel it in my bones. This isn’t progress. This is a slow suffocation with a receipt.

Lynsey Tyson

December 21, 2025 AT 01:30I never knew there were two kinds of generics until I read this. I just assumed they were all the same. Now I always ask my pharmacist if it’s made by the brand company. Last time I did, they looked surprised but then gave me the cheaper one. I saved $15 that month. Small win, but I’ll take it. Thanks for explaining this so clearly.

Edington Renwick

December 21, 2025 AT 16:58Wow. Just wow. The fact that people are actually *happy* about this is the most depressing thing I’ve read all week. We’ve normalized corporate manipulation as ‘consumer benefit.’ We don’t demand systemic change-we just learn to play the rigged game better. You’re not saving money, you’re just being allowed to breathe a little longer before the noose tightens again. This isn’t a win. It’s a trap with a discount tag.

Sarah McQuillan

December 22, 2025 AT 17:31Okay but let’s be real-this whole system is just America’s way of pretending we have a free market. In Canada, they negotiate drug prices. In the UK, they just set them. Here? We let Big Pharma write the rules and then pat ourselves on the back for ‘shopping smart.’ The authorized generic? That’s not innovation. That’s a loophole exploited by the same people who lobbied to kill price negotiation in Medicare. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy counter.

anthony funes gomez

December 24, 2025 AT 13:10It is imperative to recognize the structural asymmetries embedded within the NDA-ANDA dichotomy: the authorized generic, by virtue of its origin under the original NDA, circumvents bioequivalence requirements and regulatory latency, thereby creating a temporal arbitrage opportunity that destabilizes the incentive structure of the Hatch-Waxman framework. The 180-day exclusivity, while ostensibly a reward for litigation risk, becomes functionally neutered when the originator deploys a co-located, co-manufactured, co-formulated clone-thereby collapsing the price elasticity curve prior to true generic entry. This is not market efficiency-it is regulatory arbitrage masquerading as consumer welfare.

pascal pantel

December 25, 2025 AT 17:56Let’s cut through the noise. The FTC data is cherry-picked. Authorized generics only drop prices when the brand company wants them to. They’re not here to help you-they’re here to prevent you from getting a *real* generic that could undercut them entirely. The 180-day window? A distraction. The real game is delaying competition until the patent expires and then flooding the market with their own version so no one else can make money. This isn’t competition. It’s a coordinated price suppression strategy. And you’re celebrating it like it’s a gift.

Gloria Parraz

December 26, 2025 AT 04:11This is one of those rare moments where the system actually works-sort of. I used to pay $90 a month for my thyroid med. Now I get the authorized generic for $32. I didn’t have to switch plans, fight my insurer, or file an appeal. I just asked. And it worked. I know it’s not perfect. I know the corporations are still playing games. But for once, the game gave me something. And I’m not going to apologize for taking it.

Sahil jassy

December 27, 2025 AT 01:56Bro this is gold 😎 I’m from India and we have generics everywhere but never knew the US had this twist. So brand makes its own generic to fight its own brand? That’s next level. But hey if it cuts my cost I’m all for it. Ask your pharmacist next time. Simple as that. 🙌

Kathryn Featherstone

December 28, 2025 AT 11:28I never thought about how the same factory makes both versions. That’s kind of mind-blowing. I always assumed generics were made in different places, maybe even overseas. But if it’s the exact same pill, just a different label… I guess I’ve been paying extra for branding this whole time. I’ll be asking next time.

Henry Marcus

December 28, 2025 AT 18:24EVERYTHING YOU’RE TOLD IS A LIE. Authorized generics? That’s not competition-that’s a psyop. The FDA, the DEA, the big pharma CEOs-they’re all in on it. They let you think you’re saving money, but the real goal is to normalize dependency on a system that’s designed to keep you broke. Watch what happens after 2026-when the next patent cliff hits. The authorized generics will vanish overnight. And you’ll be left wondering why your insulin just jumped back to $400. This isn’t a market. It’s a psychological operation. They’re not lowering prices-they’re conditioning you to accept less.