When a generic drug company wants to prove its product works just like the brand-name version, it doesn’t need to run a massive clinical trial with thousands of patients. Instead, it uses a clever, efficient method called a crossover trial design. This approach is the gold standard for bioequivalence studies - the tests that allow generic drugs to hit the market faster and cheaper without sacrificing safety or effectiveness.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Testing

Imagine you’re testing two painkillers: one brand-name and one generic. In a parallel study, half the people get the brand, half get the generic, and you compare the average results. But people vary wildly - age, metabolism, liver function, even what they ate that morning. That noise makes it harder to see if the drugs are truly the same. In a crossover design, each person takes both drugs - one after the other. You’re not comparing John to Mary. You’re comparing John’s response to Drug A versus John’s response to Drug B. That cuts out the noise from person-to-person differences. It’s like using yourself as your own control. The result? You need far fewer people to get the same statistical power. Studies show you can cut your sample size by up to six times compared to a parallel design when individual differences are big. That’s why over 89% of bioequivalence studies submitted to the FDA in 2022 and 2023 used crossover designs. It’s not just popular - it’s required by regulatory agencies for most drugs.The Standard 2×2 Crossover: AB/BA

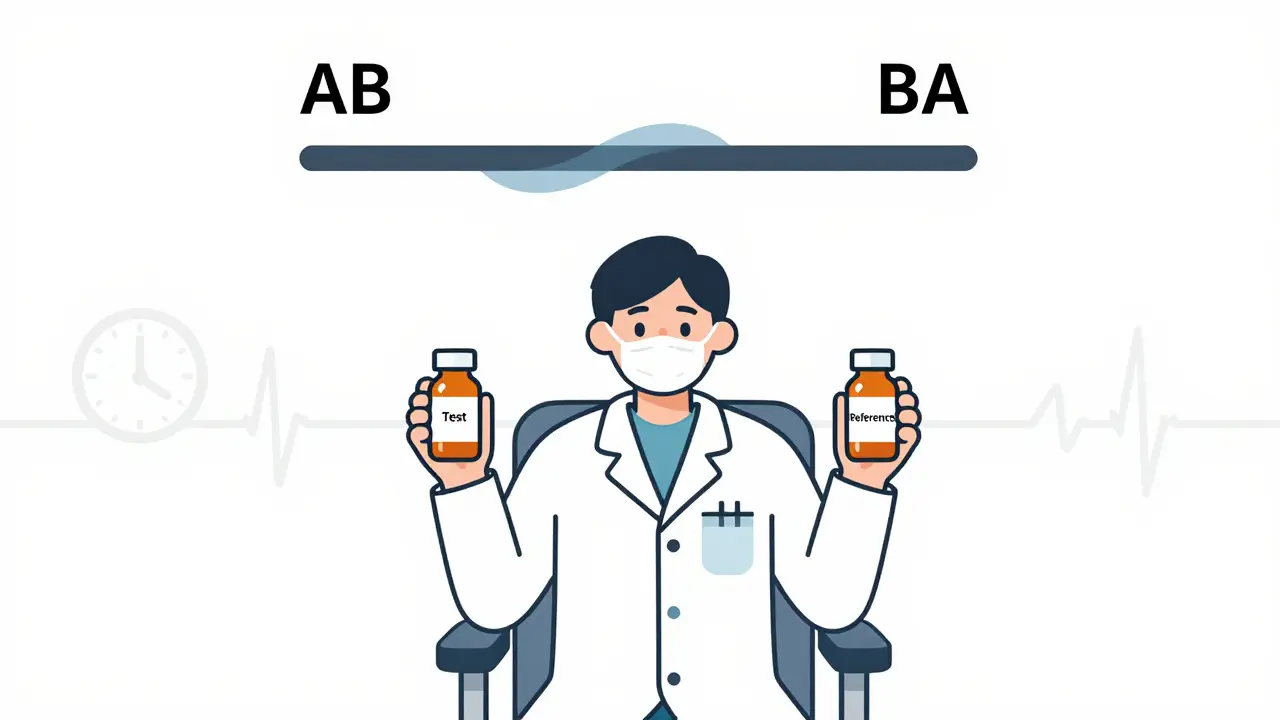

The most common setup is the two-period, two-sequence (2×2) crossover. Participants are split into two groups. One group gets the test drug first, then the reference (brand) drug after a break. The other group does the reverse: reference first, then test. This is called the AB/BA design. The key? The washout period. Between doses, there’s a waiting time - usually at least five elimination half-lives of the drug. That’s how long it takes for the drug to clear from the body so it doesn’t mess up the second period. If you don’t wait long enough, leftover drug from the first dose can skew the second. That’s called a carryover effect, and it’s one of the most common reasons studies get rejected. For example, if a drug has a half-life of 8 hours, you need at least 40 hours (5 × 8) between doses. For longer-acting drugs like some antidepressants or anticonvulsants, that washout could stretch to weeks. That’s why crossover designs don’t work for drugs with half-lives longer than two weeks - you’d be waiting months just to finish one study.What Happens With Highly Variable Drugs?

Not all drugs behave the same. Some - like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain epilepsy meds - show huge differences in how they’re absorbed from person to person. That’s called high intra-subject variability (intra-subject CV > 30%). In a standard 2×2 design, you’d need hundreds of people to detect a difference, which isn’t practical. That’s where replicate designs come in. Instead of two periods, you use four. There are two types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Test drug once, reference drug twice. This lets you estimate variability for the reference.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Each drug is given twice. This gives you variability estimates for both test and reference.

How the Data Is Analyzed

It’s not enough to just give people the drugs and measure blood levels. You need to model the data right. The standard approach uses linear mixed-effects models in software like SAS or R. The model checks three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order (AB vs. BA) influence results? If yes, maybe the washout wasn’t long enough.

- Period effect: Did results change just because it was period 2? Maybe people got better at swallowing pills or were less stressed.

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the test and reference drugs?

Real-World Wins and Woes

One company saved $287,000 and eight weeks by switching from a parallel to a 2×2 crossover design for a generic warfarin study. With an intra-subject CV of 18%, they only needed 24 people. A parallel design would’ve required 72. But another team lost $195,000 and six months. They tested a highly variable drug with a 42% CV using a standard 2×2 design. They assumed a 24-hour washout was enough. It wasn’t. Residual drug carried over. The data was useless. They had to restart with a 4-period replicate design. On Reddit’s clinical trials forum, 78% of respondents preferred crossover designs for standard studies. But 68% said replicate designs prevented study failure - even though they cost 30-40% more.What’s Changing Now?

Regulators are adapting. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs - like digoxin or levothyroxine - where tiny differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to make full replicate designs the default for all highly variable drugs in its 2024 update. There’s also a rise in adaptive designs. Instead of fixing the sample size upfront, some studies start with a small group, analyze early results, and then decide whether to add more participants. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions used this method - up from 8% in 2018.When Crossover Designs Don’t Work

Crossover isn’t magic. It fails when:- The washout period is too short - residual drug contaminates the second period.

- The drug has a half-life longer than two weeks - waiting for clearance isn’t feasible.

- The condition being treated changes over time - like depression or arthritis - so the patient’s baseline shifts between periods.

- There’s a learning effect - patients respond better the second time just because they know what to expect.

What You Need to Get It Right

If you’re designing or reviewing a bioequivalence study, here’s what matters:- Randomize by sequence, not by individual. Don’t just assign people to drugs - assign them to AB or BA groups.

- Validate washout periods with literature or pilot data. Don’t guess.

- Test for carryover in your statistical model. If sequence-by-treatment interaction is significant, your design is flawed.

- Use the right software. Phoenix WinNonlin has built-in templates. R packages like ‘bear’ are powerful but need coding skills.

- Don’t ignore missing data. If someone drops out after the first period, you lose their entire control. That breaks the whole advantage of crossover.

Why This Matters

Crossover trial designs are the backbone of generic drug approval. They make life-saving medications affordable without compromising safety. They’re efficient, scientifically sound, and backed by decades of regulatory experience. But they’re also unforgiving. One missed washout, one flawed model, and the whole study collapses. As complex generics - like biosimilars and inhalers - become more common, the demand for advanced replicate designs will only grow. The future of bioequivalence isn’t about bigger studies. It’s about smarter ones.What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control, eliminating inter-subject variability. This dramatically increases statistical power and allows researchers to use far fewer participants - sometimes as few as one-sixth the number needed in a parallel design - while still detecting small differences between drugs.

What is a 2×2 crossover design?

A 2×2 crossover design is the most common setup in bioequivalence studies. Participants are randomly assigned to one of two sequences: either Test then Reference (AB), or Reference then Test (BA). Each participant receives both treatments, with a washout period between. This design balances order effects and allows direct within-subject comparison.

Why are washout periods so important in crossover trials?

Washout periods ensure that the drug from the first treatment period is completely cleared from the body before the second treatment begins. If residual drug remains, it can interfere with measurements in the second period, creating carryover effects that bias results. Regulatory guidelines require washouts to last at least five elimination half-lives of the drug.

When is a replicate crossover design used?

Replicate crossover designs (TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs, where the intra-subject coefficient of variation exceeds 30%. These designs allow regulators to estimate within-subject variability for both the test and reference products, enabling reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE) approaches that adjust the acceptance range based on how variable the reference drug is.

What are the regulatory acceptance criteria for bioequivalence?

For most drugs, bioequivalence is demonstrated when the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) of AUC and Cmax falls between 80.00% and 125.00%. For highly variable drugs using RSABE, the range can be widened to 75.00%-133.33%, provided the reference drug’s variability justifies it. These limits are set by the FDA and EMA.

Hanna Spittel

January 1, 2026 AT 15:50Brady K.

January 2, 2026 AT 23:34Kayla Kliphardt

January 4, 2026 AT 21:36John Chapman

January 5, 2026 AT 17:26Urvi Patel

January 5, 2026 AT 18:03anggit marga

January 7, 2026 AT 06:49Joy Nickles

January 8, 2026 AT 19:58Emma Hooper

January 10, 2026 AT 13:09Martin Viau

January 10, 2026 AT 20:39Marilyn Ferrera

January 12, 2026 AT 00:54Robb Rice

January 13, 2026 AT 06:34