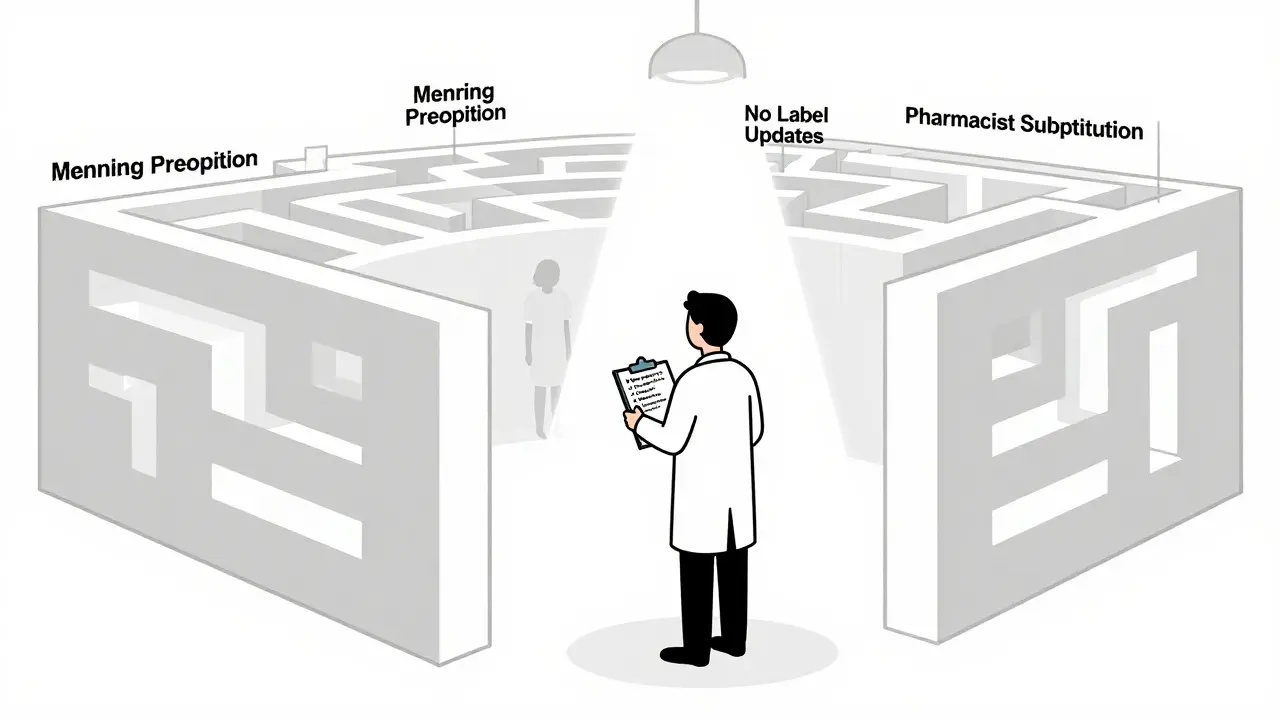

When you prescribe a generic medication, you might think you’re doing the right thing-saving your patient money, following guidelines, cutting costs. But in 2025, that simple act carries more legal risk than ever before. Physician liability for generic drug prescriptions isn’t just about medical judgment anymore. It’s about navigating a legal maze where the drugmaker can’t be sued, the pharmacist can substitute without telling you, and if something goes wrong, you’re often the only one left standing in court.

Why Generic Prescriptions Are Now a Legal Minefield

In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in PLIVA v. Mensing that generic drug manufacturers can’t be held liable for failing to update warning labels. Why? Because federal law forces them to use the exact same label as the brand-name version. They can’t change it on their own. That ruling was solidified in 2013 with Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett, where a woman lost 65% of her skin after taking a generic anti-inflammatory and was left permanently disfigured. She couldn’t sue the maker of the generic drug. The court said they weren’t allowed to change the label, so they couldn’t be blamed for not warning her. That decision created what lawyers now call the “Mensing/Bartlett Preemption.” It shut the door on most lawsuits against generic manufacturers. So when a patient is harmed, who do they sue? Often, it’s the doctor who wrote the prescription. You might think, “But I didn’t make the drug.” And you’re right. But under current law, your role as the prescriber means you’re now the last line of defense. If the label doesn’t warn about a rare but deadly side effect-and you didn’t tell your patient either-you could be held responsible.The Substitution Problem: Pharmacists Can Switch Without Telling You

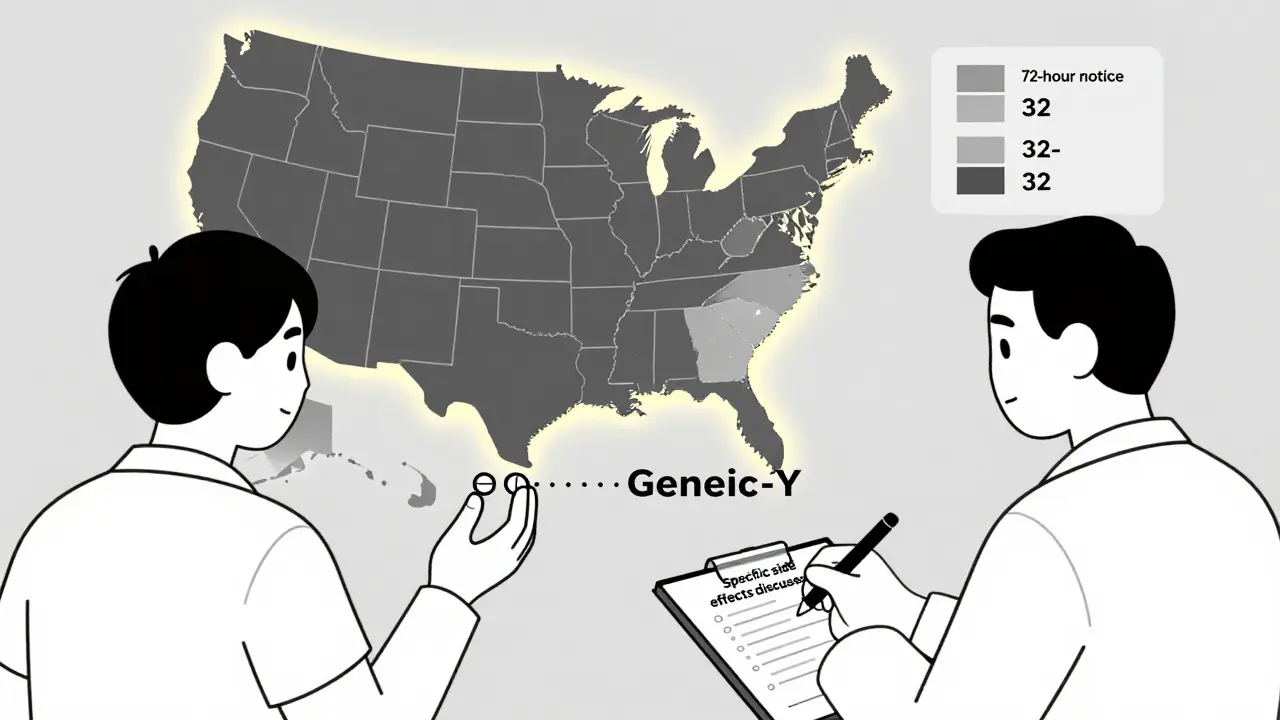

Forty-nine states allow pharmacists to swap a brand-name drug for a generic version without asking you, unless you write “dispense as written” or “do not substitute” on the prescription. In 32 states, the pharmacist must notify you within 72 hours. In 17 states? They don’t have to tell you anything. That means you could prescribe Brand-X, and the patient walks out with Generic-Y. You never know. And if Generic-Y causes an unexpected reaction-say, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a life-threatening skin condition-you’re the one the patient’s lawyer will track down. One Texas primary care doctor told me about a case where a patient developed severe liver damage after switching to a generic diabetes drug. The label hadn’t been updated to include liver toxicity warnings. The manufacturer couldn’t be sued. The pharmacist didn’t notify the doctor. The patient sued the physician for not warning them about side effects. The doctor settled for $280,000-even though they’d never heard of that specific risk before.It’s Not About the Drug-It’s About the Warning

The legal standard for physician liability hasn’t changed: you must meet the standard of care. That means you need to know the risks of the drugs you prescribe, warn patients about serious side effects, and document that conversation. Here’s the problem: generic drugs often have less clinical data than brand-name versions. Many physicians rely on the brand-name label for safety info. But if the brand-name label gets updated with new warnings, generic manufacturers aren’t required to follow suit. So you could be prescribing a drug based on outdated safety info. The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals made a small crack in the wall in 2023 with Johnson v. Teva Pharmaceuticals. They ruled that if a brand-name manufacturer updates its label with new safety info, and the generic manufacturer ignores it, the generic maker *can* be sued. But that’s the only exception-and it’s narrow. Most cases still fall under the old rule: no liability for generic makers. That puts the burden squarely on you. If you prescribe a drug with known risks-drowsiness, liver damage, skin reactions-you must tell the patient. And you must write it down.

What You Should Be Documenting (And What You Shouldn’t)

A generic note like “medication discussed” won’t cut it anymore. Insurance companies and courts are looking for specifics. The American Medical Association recommends this language in your notes:I have discussed potential side effects of [medication], including [specific side effects], and advised you to avoid [specific activities] while taking this medication. I explained that this drug may be dispensed as a generic equivalent, and that the label may not reflect the most recent safety updates.Epic Systems, the most widely used electronic health record platform, now requires physicians to fill out a mandatory “Generic Substitution Counseling” field in every prescription since 2021. Skip it? Your chart gets flagged. In a lawsuit, that flagged chart could be your best defense-or your worst mistake. A 2023 report from Medical Risk Management, Inc. found that physicians who document specific counseling about generic substitution reduce their liability exposure by 58%. Those who just write “medication reviewed”? Their risk stays high.

When to Say “Dispense as Written”

Not every drug is safe to substitute. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index-where small changes in dose can cause serious harm-you should always write “dispense as written.” These include:- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Levothyroxine (thyroid hormone)

- Phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate (anti-seizure drugs)

- Lithium (mood stabilizer)

- Cyclosporine and tacrolimus (transplant drugs)

Insurance Premiums Are Rising-And So Are Lawsuits

The number of lawsuits targeting physicians over generic drug injuries jumped 37% between 2014 and 2019, according to the American Bar Association. That trend hasn’t slowed. In 2023, the average settlement for these cases was $327,500. Twelve of 47 documented cases in the American College of Physicians’ database resulted in settlements that high. Your malpractice insurance isn’t ignoring this. The American Professional Agency reports a 7.3% premium surcharge for physicians who prescribe generics without documenting specific counseling. That’s on top of the 22.7% increase in primary care premiums since 2013. A 2022 AMA survey of 1,200 physicians found that 68% feel more anxious about prescribing generics. Forty-two percent admit they sometimes prescribe the more expensive brand-name drug-just to avoid liability, even when the patient can’t afford it.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to stop prescribing generics. But you need to change how you do it.- Always document specific counseling-don’t just say “medication discussed.” Name the side effects and the activities to avoid.

- Use “dispense as written” for narrow therapeutic index drugs. Don’t assume the pharmacist knows the risk.

- Check the FDA’s latest safety alerts before prescribing. If the brand-name label changed, assume the generic hasn’t.

- Ask patients if they’ve had issues with generics before. Some people react differently to fillers or binders in generic versions.

- Know your state’s substitution laws. Some require notification. Others don’t. Be aware.

Ron Williams

December 15, 2025 AT 03:12Man, this is wild. I’ve been prescribing generics for 15 years and never thought twice about it. Now I’m sweating bullets every time I hit ‘send’ on a script. The fact that the manufacturer can’t be sued but I can? That’s not medicine-that’s legal Russian roulette.

And don’t get me started on pharmacists swapping without telling you. I had a patient come in last month with a rash after switching to a generic statin. I had no idea. The pharmacy didn’t notify me. The label didn’t warn me. Now I’m the bad guy? That’s not justice. That’s a system designed to make doctors the fall guy.

Dave Alponvyr

December 16, 2025 AT 12:48So let me get this straight-you’re telling me I have to lecture every patient about generic labels that aren’t even updated? And if I don’t, I’m on the hook? Cool. I’ll just start charging $500 per script just to cover the time I’m wasting playing lawyer.

Colleen Bigelow

December 17, 2025 AT 07:37THIS IS THE NEW WORLD ORDER. Big Pharma owns the FDA, the courts, and now they’ve rigged the system so doctors take the fall while they rake in billions. You think this is about safety? No. It’s about profit. They don’t care if you get skin peeled off-you’re just a disposable cog. They’ve got lobbyists in D.C. writing laws to protect their bottom line while you’re stuck with a $300k settlement and a ruined career.

And don’t tell me ‘document everything’-they’re watching your EHR. They’re tracking your keystrokes. They’re building dossiers on you. This isn’t medicine anymore. It’s surveillance capitalism with a stethoscope.

Cassandra Collins

December 18, 2025 AT 01:52ok so like… i just found out my dr prescribed me generic lipitor and i had a stroke?? and no one told me?? and now im like… why did they even make this drug if they knew it could kill people?? i feel so betrayed. like my dr is just some pawn and big pharma is the real villain?? why dont they just ban all generics??

Mike Smith

December 18, 2025 AT 03:04As a physician who’s been practicing for over two decades, I can tell you that this isn’t a new problem-it’s just been amplified by legal precedent and systemic neglect. The Supreme Court’s rulings weren’t about patient safety; they were about corporate liability shielding. And yes, it’s unfair. But the solution isn’t to stop prescribing generics-it’s to demand legislative reform and to document with surgical precision.

I now use a standardized script for every generic prescription: ‘This medication may be substituted by your pharmacist. The label you receive may not reflect the most recent safety updates issued by the brand-name manufacturer. I’ve reviewed the known risks with you, including [list]. If you experience [symptom], stop immediately and call.’

It takes 90 seconds. It’s not optional anymore. And yes, I’ve had patients thank me for being transparent. That’s the point: we’re not just doctors. We’re advocates. And in this broken system, advocacy is the only shield we have left.

Billy Poling

December 18, 2025 AT 09:30It is imperative to note, with the utmost gravity and scholarly rigor, that the legal doctrine of preemption as articulated in PLIVA v. Mensing and subsequently reinforced in Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett constitutes a fundamental abdication of tort liability by the pharmaceutical industry, thereby creating a vacuum of accountability that has been catastrophically filled by the prescribing physician, who, by virtue of their professional licensure and fiduciary duty, is now functionally compelled to assume the role of de facto regulatory compliance officer, despite possessing neither the statutory authority nor the institutional resources to enforce label updates or monitor pharmacological substitution protocols across state lines.

Furthermore, the electronic health record mandates imposed by Epic Systems, while ostensibly designed to enhance patient safety, function as a form of algorithmic coercion, wherein the physician’s clinical autonomy is subordinated to corporate software architecture that prioritizes litigation defense over therapeutic efficacy. The requirement to populate a mandatory ‘Generic Substitution Counseling’ field-while statistically correlated with a 58% reduction in liability exposure-nonetheless imposes an undue administrative burden that contributes to physician burnout, a phenomenon now recognized by the American Medical Association as a public health crisis.

It is therefore not merely a matter of clinical caution but of existential professional survival: every prescription must now be accompanied by a legally defensible narrative, a forensic record of informed consent that transcends the traditional boundaries of medical practice and enters the domain of legal testimony. The physician, once a healer, is now a defendant-in-waiting.

Aditya Kumar

December 18, 2025 AT 21:58Too much work. I just write ‘medication discussed’ and hope for the best. If someone gets hurt, it’s not my fault. I didn’t make the drug. I’m just trying to get through my shift.

Elizabeth Bauman

December 20, 2025 AT 06:21Okay, let’s be real-this is all because the U.S. let Big Pharma write the rules. In Europe, generic makers HAVE to update their labels. In Canada, pharmacists are required to notify the prescriber. But here? We’re the only country where the doctor gets sued because a corporation didn’t want to spend $500 on a label change.

And don’t even get me started on how the FDA lets this happen. They’re supposed to protect us, but they’re just letting corporations off the hook. This isn’t free market-it’s corporate feudalism. And guess who’s paying the price? The doctors. The patients. Everyone but the CEOs in their penthouses.

So yes, document everything. Say ‘dispense as written’ for warfarin. Check the FDA alerts. But also-vote. Call your rep. This isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a political one. And if we don’t fix it, next year it’ll be your IV antibiotics, then your insulin, then your asthma inhaler. They’re coming for all of us. And they’re counting on you to stay silent.