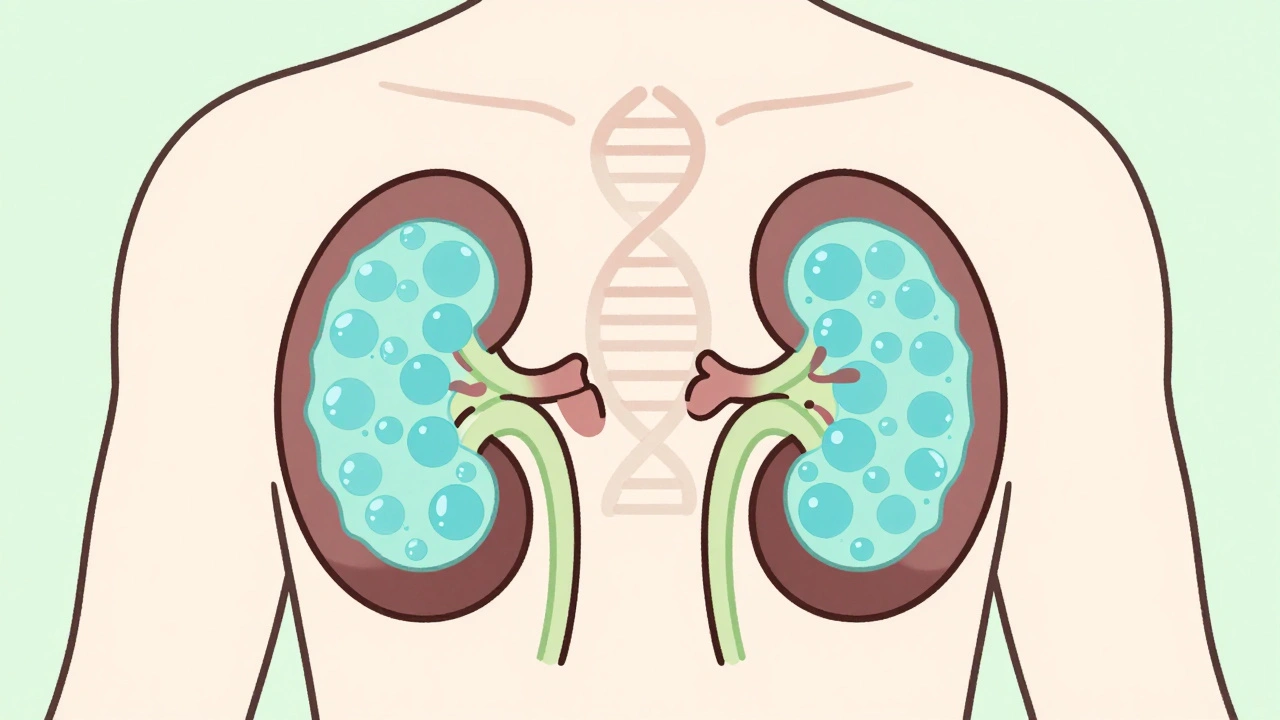

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) isn’t just about fluid-filled sacs in the kidneys. It’s a silent, inherited storm that slowly destroys kidney function over decades. In the U.S., about 600,000 people live with it-many unaware until their kidneys start failing. Unlike infections or lifestyle-driven conditions, PKD is coded into your DNA. You don’t catch it. You inherit it. And if you have it, there’s a 50% chance you’ll pass it on to each child.

Two Types, One Root Cause

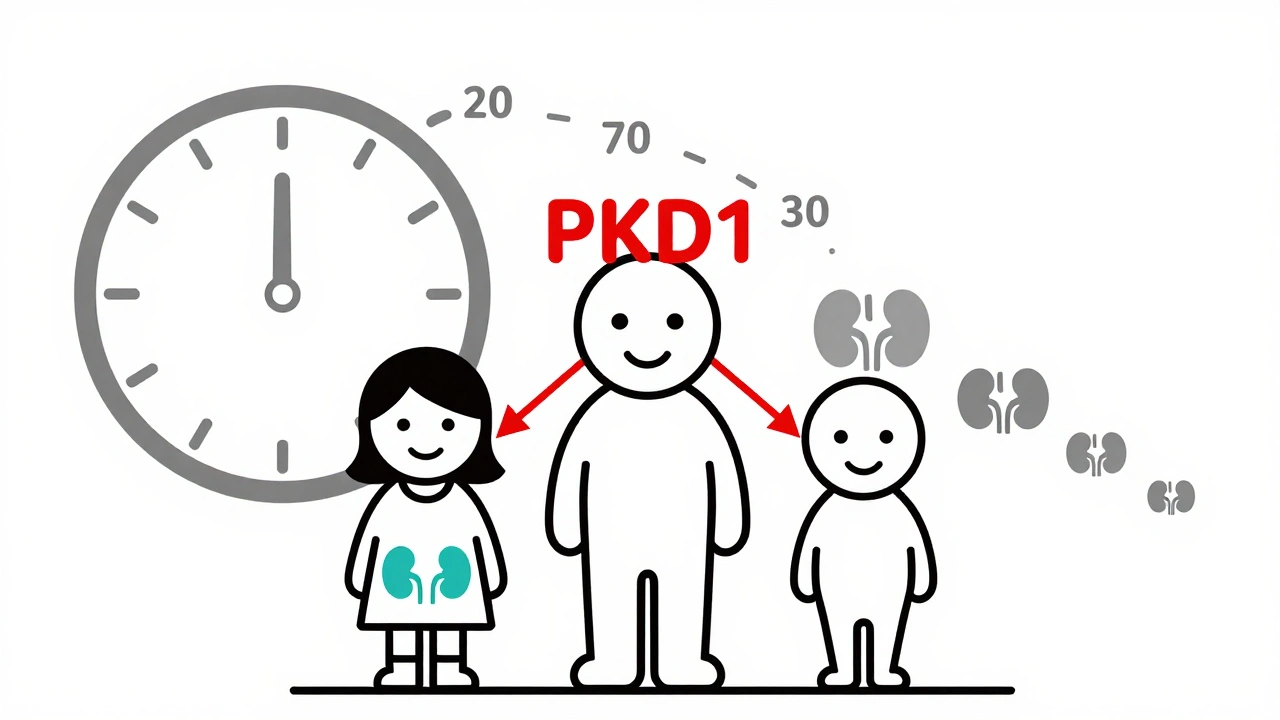

There are two main forms of PKD: autosomal dominant (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive (ARPKD). They’re not just different in severity-they’re different in how they show up, who gets them, and when.ADPKD is the big one. It makes up over 98% of all cases. It’s caused by mutations in either the PKD1 or PKD2 gene. PKD1 mutations are more aggressive-people with this version often reach kidney failure by their 50s or 60s. PKD2 moves slower. Some people with PKD2 never need dialysis. About 10% of ADPKD cases happen without any family history. That’s a new mutation, meaning no one else in your family had it. But now, you might pass it on.

ARPKD is rare-about 1 in 20,000 births. It needs two bad copies of the PKHD1 gene, one from each parent. Parents usually don’t know they carry it until their baby is born with enlarged kidneys or breathing problems. Babies with ARPKD often show symptoms right after birth. Some don’t survive infancy. Others live into childhood or adulthood, but they frequently face liver complications too.

What Happens Inside Your Kidneys

Healthy kidneys filter waste, balance fluids, and control blood pressure. In PKD, cells that should form tiny tubes start growing cysts-fluid-filled bubbles that multiply like weeds. Over time, these cysts swell, crush healthy tissue, and take over. Kidneys that normally weigh about half a pound can balloon to 30 pounds. That’s the weight of a large cat.As cysts grow, kidney function drops. The body loses its ability to clean blood, regulate salt, or make enough red blood cells. High blood pressure is almost universal in ADPKD-it’s not a side effect, it’s a direct result of damaged kidney tissue. Many people first notice PKD when they get a routine blood test and find their creatinine is high, or an ultrasound shows cysts they didn’t know were there.

Some people have symptoms in their 20s. Others don’t feel anything until their 40s. The variation is huge. Why? Because even with the same gene mutation, other genes, lifestyle, and environment play a role. One person might have a few slow-growing cysts. Another might have hundreds that explode in growth by age 35. No one can predict exactly how fast it will go.

Diagnosis: When and How

If you have a parent with ADPKD, you have a 50% chance of inheriting it. Doctors don’t wait for symptoms to show up. They use imaging. For someone aged 30-39 with a family history, finding at least 10 cysts on an ultrasound confirms ADPKD. MRI is more sensitive-it can spot tiny cysts years before ultrasound can. CT scans are used too, but they involve radiation, so they’re not the first choice.Genetic testing is now common. A blood or saliva sample can check for mutations in PKD1, PKD2, or PKHD1. These tests cost around $1,200 and are offered by labs like Invitae and Ambry Genetics. They’re not always needed-if your family history is clear and imaging confirms it, you might skip it. But if you’re thinking about having kids, or if your symptoms don’t match the usual pattern, testing gives answers.

For ARPKD, diagnosis often happens before birth. Prenatal ultrasounds might show unusually large kidneys in the fetus. After birth, doctors check liver function too, because PKHD1 mutations affect both organs.

Managing the Disease: What Actually Works

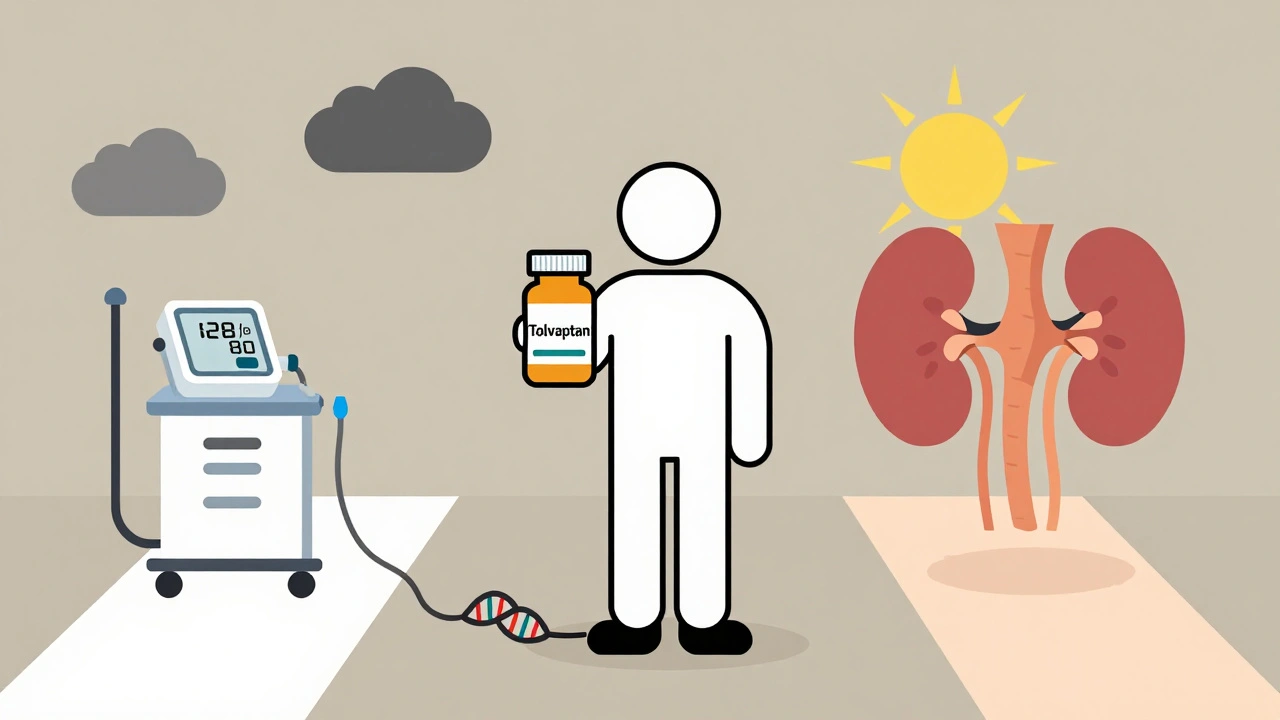

There’s no cure. But you can slow it down. And many people live full lives for decades.Control your blood pressure. This is the single most important thing. The target? Below 130/80 mmHg. Some doctors push for even lower-110/75-if you’re young and have fast-progressing disease. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are the go-to drugs. They don’t just lower pressure-they protect kidney tissue. One patient in Houston started on an ARB at 28, after his dad went on dialysis. At 45, his kidney function is still at 65%. That’s not luck. That’s early action.

Take tolvaptan (Jynarque). Approved by the FDA in 2018, this is the first drug that targets the disease itself, not just symptoms. It blocks a hormone that makes cysts grow. In clinical trials, it slowed kidney decline by about 1.3 mL/min per year. That’s not a cure-but it can delay dialysis by 5 to 10 years. The catch? It costs around $115,000 a year. Insurance often covers it if you’re at high risk for rapid decline, based on age, kidney size, and gene type.

Watch your diet and fluids. No magic diet cures PKD, but reducing salt helps control blood pressure. Avoid excessive caffeine and alcohol-they can raise blood pressure and stress the kidneys. Drink enough water. Some studies suggest staying well-hydrated might slow cyst growth, especially in hot climates like Houston, where dehydration is easy.

Monitor kidney function. Get your eGFR tested at least once a year. If it drops below 60, test every 3 months. Track your numbers. Know your trend. If your eGFR falls below 30, start talking to a transplant center. Wait times for a kidney in the U.S. average 3-5 years. Getting on the list early matters.

Complications: More Than Just Kidneys

PKD doesn’t stop at the kidneys. Cysts can form in the liver, pancreas, and even the brain. About 20% of people with ADPKD develop brain aneurysms. If you have a family history of ruptured aneurysms, your doctor may recommend a brain MRI. It’s not routine-but it could save your life.Pain is the #1 complaint. It’s not just back pain. It’s deep, constant, and often misunderstood. In a 2023 survey of 1,245 PKD patients, 78% said chronic pain was their biggest challenge. Some get cyst infections that require antibiotics. Others have kidney stones. High blood pressure leads to heart strain. Many end up with heart valve issues or mitral valve prolapse.

Emotionally, it’s heavy. One Reddit user wrote, “It took seven years and three doctors to get diagnosed-even though my dad was on dialysis.” Delayed diagnosis is common. People think it’s just back pain or stress. By the time they find out, damage is done.

The Future: What’s on the Horizon

Research is moving fast. Tolvaptan was a breakthrough, but it’s not perfect. Side effects include extreme thirst, frequent urination, and liver stress. New drugs are coming.Lixivaptan is in phase 3 trials and may be similar to tolvaptan but with fewer side effects. Bardoxolone methyl showed promise in early studies, improving kidney function by nearly 5 mL/min over 48 weeks. These aren’t cures-but they’re steps forward.

Gene therapy is still experimental, but scientists are exploring ways to silence the faulty PKD1 gene. CRISPR-based approaches are being tested in labs. It’s years away, but it’s real.

For now, the best strategy is early detection, strict blood pressure control, and staying informed. If you have PKD, join a support group. Talk to others who get it. Knowledge is power. And in PKD, power means time.

When It’s Time for Dialysis or Transplant

By age 70, about 75% of people with ADPKD will need dialysis or a kidney transplant. That sounds scary-but it’s not the end. Kidney transplants work well for PKD patients. The cysts don’t come back in the new kidney. Your body just stops making them.Transplant success rates are high-over 90% after one year. The biggest hurdle? Wait time. If you’re blood type O, you might wait longer. If you’re in a big city like Houston, you might get matched faster. Talk to your nephrologist early. Get evaluated. Don’t wait until you’re sick.

Some patients choose to start dialysis earlier than required. It’s not about saving kidneys-it’s about staying strong. Dialysis keeps you alive, but it’s exhausting. A transplant gives you back your life.

Living With PKD: Real Life, Real Choices

I’ve talked to people who’ve had PKD for 30 years. Some work full-time. Some run marathons. Others can’t leave the house because of pain. It’s not about the diagnosis. It’s about what you do with it.Don’t ignore your blood pressure. Don’t skip checkups. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse before acting. If you have a family history, get screened. If you’re diagnosed, learn everything you can. Ask about genetic testing for your kids. Talk to a dietitian. Join a support group.

PKD doesn’t define you. But how you manage it? That does.

Is polycystic kidney disease curable?

No, there is currently no cure for polycystic kidney disease (PKD). Treatments focus on slowing progression and managing complications like high blood pressure and pain. The FDA-approved drug tolvaptan can delay kidney function decline in some patients, but it doesn’t stop the disease. Research into gene therapies and new drugs is ongoing, but no cure exists yet.

Can you get PKD if no one in your family has it?

Yes. About 10% of autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) cases result from a new, spontaneous mutation-meaning neither parent carries the faulty gene. This is called a de novo mutation. The person then becomes the first in their family to have PKD and can pass it on to their children with a 50% chance.

How is PKD different from simple kidney cysts?

Simple kidney cysts are common in older adults and usually harmless-they don’t affect kidney function or cause symptoms. PKD cysts are numerous, inherited, and grow aggressively over time, destroying healthy kidney tissue. PKD cysts are linked to specific gene mutations (PKD1, PKD2, or PKHD1), while simple cysts have no known genetic cause.

Does PKD affect life expectancy?

It can, but many people live into their 70s or 80s with proper management. About 50% of ADPKD patients reach kidney failure by age 60. With timely dialysis or transplant, life expectancy returns close to normal. The biggest risks come from uncontrolled high blood pressure, heart complications, or undetected brain aneurysms-not the cysts themselves.

Can you prevent PKD if it runs in your family?

You can’t prevent inheriting the gene, but you can prevent complications. If you have a family history, get tested early. Control your blood pressure aggressively. Avoid smoking, excessive salt, and NSAIDs like ibuprofen. Stay hydrated. These steps can delay kidney damage by decades. Genetic counseling can also help you understand risks before having children.

Gillian Watson

December 2, 2025 AT 05:32Shofner Lehto

December 2, 2025 AT 21:44Yasmine Hajar

December 4, 2025 AT 08:42Jake Deeds

December 4, 2025 AT 12:45John Filby

December 5, 2025 AT 14:12Elizabeth Crutchfield

December 6, 2025 AT 22:05Ashley Elliott

December 8, 2025 AT 14:56Augusta Barlow

December 9, 2025 AT 09:07Joe Lam

December 10, 2025 AT 22:17Jenny Rogers

December 11, 2025 AT 22:00Rachel Bonaparte

December 13, 2025 AT 16:53Scott van Haastrecht

December 14, 2025 AT 09:55Chase Brittingham

December 15, 2025 AT 21:21Bill Wolfe

December 17, 2025 AT 16:40jagdish kumar

December 19, 2025 AT 01:14zac grant

December 19, 2025 AT 02:08